tiOPF |

Free, Open Source Object Persistence Framework for Free Pascal & Delphi |

6. The Adaptor Pattern and Database Independence

Authors note

This chapter is a cut-and-paste from an article printed in The Delphi Magazine. It must be re-written in the context of the tiOPF but I have included it here because I have run out of time to edit it as necessary. The general principal is vital to the framework, but the examples in the article are not totally relevant. You will notice that I step painfully through the development of a Factory again, this is because this article was written as a stand alone piece, and not as a part of a larger work. Sorry for the repetition, but I can't just chop it out without making other structural changes.

The tiOPF framework code that uses the Adaptor can be found in the <tiopf>\Core\ directory. The abstract classes TtiDatabase and TtiQuery can be found in tiQuery.pas. The concrete implementation can be found in tiQueryDOA.pas, tiQueryIBX.pas and so on.

I hope the material is of use to you, and as I said, keep an eye out for updates.

Introduction

The Delphi Component Pallet is growing with every release of Delphi. Apart from the GUI controls we have had since Delphi 1, we now have several non-visual controls, all performing the same basic task, to choose from.

For example:

- For SQL database access we can choose between the BDE controls (TDatabase and TQuery) and ADO. If we are targeting a specific database, we may want to bypass a generic data connection layer and go directly to the database's API using a family of controls like IBObjects for Interbase, or DOA for Oracle.

- For Internet connection, you may have started your project with an early version of Delphi using the FastNet components, but now want to move up to WinShoes, or the more recent Indy components.

- For data compression, you may have started your project using the ZLib compression algorithm that is supplied on the Delphi CD, and now want to change to the more widely used Zip format.

- You may have started a project with no data encryption, but changed requirements mean you have to add encryption without breaking any existing systems.

- For XML parsing, you can choose between building a dependency on the MSDom DLL that comes with Internet Explorer 5, or use one of the native Delphi parsers that are available on the web (this chapter was written before the official release of Delphi 6, which now contains a native XML parser).

The next section of this chapter will discuss some of the problems of building a dependency on a single vendor's component. We then take a look at what GoF say about the Adaptor Pattern and take a look at the various ways it can be implemented with Delphi. We finish by using the Adaptor to wrapper the ZLib compression library. Once we have wrappered ZLib, we examine two ways of creating concrete instances of the adapted class by using a class reference and the Factory Pattern.

How Binding to a Vendor's API Can Bite You

Say you want to use a third party component in your application to perform a task like one of those listed above. There are three ways you can use this component:

- You can drop it on a form or data module. (This technique is simple to code, but it is difficult to make changes to the application once built.)

- You can create it, use it then free it in code. (This technique is more complex to code, but easier to change the application's behaviour at compile-time.)

- You can wrapper the component in your own code giving it a standard interface at the same time, then use either a class reference variable or a Factory to create the concrete component for use. (This requires significantly more work to code, but is very versatile as the application's behaviour can be changed at compile-time or run-time.)

Dropping the component on a form or data module will work fine if there is only going to be one of them in the application. This may be the case for a FTP component where all FTP calls can be channelled through the same routine. If you want to change to another vendor's component, it is not too hard to make the necessary modification at design time and then re-compile. This technique becomes very clumsy if there are many instances of the component created at design time in different places in the application. It is difficult to use search and replace on DFM files. It will also be necessary to make changes to the units included with the application in the uses clause - this is both time consuming and error prone.

A better alternative is to create, use then free the component in code and hopefully, to route all use of the component through the same block of code. The switch from one vendor's component to another could be made by either cut & paste, or by swapping the unit containing the code that creates the component with another.

The most versatile solution is to write a component wrapper, then create the component using a class reference or Factory. This means that making the single line change where the unit that implements the appropriate concrete class in included in the project does the switch from one vendor to another. Alternatively, if a Factory is used to create the component, the change can be made at run time, which has the potential of giving the user control the behaviour of the application.

Software House & Corporate IT Departments Share the Problem

The challenge to make the right decision when selecting a component affects us in different ways depending on what sort of business we are programming for. One of my customers decided from the start that they would use Oracle so do not mind building a dependency on the DOA controls in their Delphi application. This dependency takes the form of TOracleSession and TOracleDataSet components (the DOA equivalent to TDatabase and TQuery) being littered over the application's forms and data modules. This really does not matter to them as long as they NEVER want to change databases.

The decision to drop DOA components directly onto forms and data modules did, however cause me problems as a contractor. The library of routines and components that I take from client to client could not be used because the interface of the DOA components, while very similar to the BDE equivalents contained some annoying differences.

The same problem is potentially created as soon as you drop any component that has an interface that you do not control into an application.

For example, if you want to download a file using FTP from within a Delphi application, you may start using the FastNet TNMFTP component that has an interface like this:

NMFTP1.Connect ; NMFTP1.ChangeDir( DirName : string ) ; NMFTP1.Download( RemoteFile : String ; LocalFile : string ) ;

Later, you may want to move to the Indy TIdFTP component that has an interface like this:

IdFTP1.Connect( AutoLogin : Boolean = true ) ; IdFTP1.ChangeDir( ADirName : string ) ; IdFTP1.Get( ASourceFile : String ; ADest : TStream ) ; IdFTP1.Get( ASourceFile : String ; ADestFile : String ; ACanOverWrite : Boolean = false ) ;

As you can see, there are subtle but annoying differences.

An IT department within a big company may be able to bind tightly to a suite of components and never face any problems. However, they may merge with another organisation, or take over a smaller company and be asked to integrate their information technology systems, which are based on different component vendors APIs.

A contractor or a software house with many clients will probably be forced to use a variety of different components to achieve the same result because of having to work within the different standards required by the varying clients. This is one place where the Adaptor Pattern has really worked for me.

I can use exactly the same persistence framework with my customers who use DOA as for those who use IBObjects or the BDE. I just change a single line in the project's DPR file as show below:

To configure as a BDE based application:

program AdaptorDemo; uses // The abstract class which defines the interface tiQueryAbs, // Pull in the BDE flavour of the framework tiQueryBDE ;

To configure as an IBObjects based application:

program AdaptorDemo; uses // The abstract class which defines the interface tiQueryAbs, // Pull in the IBObjects flavour of the framework tiQueryIB ;

To configure as a DOA based application:

program AdaptorDemo; uses // The abstract class which defines the interface tiQueryAbs, // Pull in the Oracle flavour of the framework tiQueryDOA ;

How this Implementation of the Adaptor Evolved

The implementation of the Adaptor we shall look at here evolved in a project I worked on early in 1999. We where using Delphi to process information contained in a relational database, then writing out a text files which where used as the input to another process. When the bulk of development was completed and we where working towards deployment we realised that our text files where several Meg in size and where too big to transfer over the slow network link we had been allocated. The obvious solution was to compress the files before sending then and to decompress them when they arrived. We started looking around for a compression component and found several on the web costing around about $100 US. We went to our project manager for approval to buy the component and where told that the budget for the project had been closed, and we could not purchase any more software. But, it's only $100 and it will probably cost 20 times that amount to write something ourselves. Sorry! But? No!

After clearing our heads in the coffee shop in the basement of the building, we realised that Delphi comes with the compression library, ZLib on the install CD. We agreed to use ZLib with the aim of replacing it with a Zip routine when the project manager's purse strings where a little looser.

After messing around with ZLib for a while, we grew sick of using it's clumsy class based, and buffer based interfaces. We wanted to be able to do something simple like

lOutputString := CompressString( pInputString );

rather than having to create a TCompressionStream or use pointers and buffers as would otherwise be required. (We look at this more closely in the section on ZLib that follows)

Wrappering looked like the way forward. We would write a method called CompressString, and hide the need to create and free a TCompressionStream under the hood. Once this was done, it would be a simple matter to extend the interface of our new ZLib compression class to compress and decompress files, streams and buffers as well as strings.

The steps we took where to create a compression class that used ZLib behind an interface designed the way we wanted it. Once this was working, we re-factored to give a pure abstract class that declares the interface we want to use, but contains no implementation. Our ZLib compression class then descends from the pure abstract and adds the functionality required. Next, we created our compression objects via a class reference then finally wrote a Factory to take care of the object creation. We also took the opportunity to create a compression class that actually did no compression. This was useful in debugging if we suspected the compression algorithm was introducing bugs.

What the GoF Book Says About The Adaptor

Page 139 of GoF tells us that the intent of the Adaptor is:

Convert the interface of a class into another interface clients expect. Adaptor lets classes work together that couldn't otherwise because of incompatible interfaces'.

They go on to give one of their usual bad example that features a graphical toolkit. (After all, not many of us build WYSIWYG editors, so how about an example that a business programmer can relate to guys?) The discussion of the graphical tool kit goes on for three pages. The persistent reader is finally rewarded as they get to page 142 where the consequences of The Adaptor are discussed in great and enlightening detail.

GoF introduce us to two ways of implementing the Adaptor Pattern. They call these Class Adaptors and Object Adaptors:

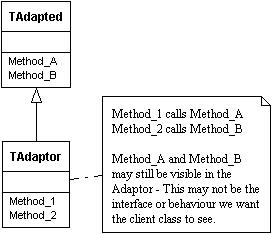

Class Adaptor

Class Adaptors use inheritance (or multiple inheritance, which we can fake with Delphi's interfaces) as shown below:

To implement GoF's Class Adaptor, we inherited from the class to be adapted and add the new methods and properties as required.

While this is an adequate solution, it is not the one I usually use. If the class to be adapted has a complex interface and we only want to adapt a few of the methods, this will do the trick. If we have several classes to adapt, and want the to inherit from the same parent class (so they can be created with a Factory), we must use an Object Adaptor. Some more advantages and disadvantages of Class Adaptors are listed below.

Advantages:

- Adaptation by inheritance means there is less code to write;

- inheritance is good when we only want to adapt part of the interface;

- inheritance means fewer classes created at run-time.

Disadvantages:

- If we have two unrelated classes that provide the same functionality, we will not be able to use a class reference or Factory to create an instance of the type we want at run-time;

- We may confuse the developers using our Adaptor, as the old interface of the adapted class will be visible as well as the newly created adapted interface.

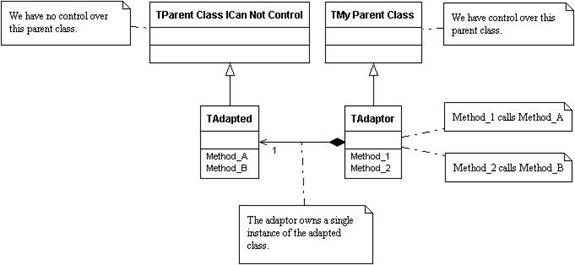

Object Adaptors

Object Adaptors require more work to implement; however the benefits are such that I think it is worth the effort. The UML of the Object Adaptor is shown below:

The key issue is that we want to have full control over the adapted class. We want to be able to specify its interface as well as its parent class so we can create instances with a Factory. This point is key to the rest of the chapter.

Adapting ZLib

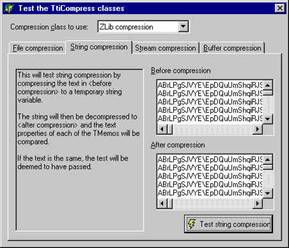

In this example, we shall construct a wrapper for ZLib that gives us control over the interface. We shall implement the Null Object Pattern by creating a compression class that does not actually do anything. Finally, we shall create these compression objects using a Factory so the behaviour of the application can be changed at runtime. The main form of this test application is show below:

The ZLib library can be found on Delphi 5's CD in \Info\Extras\ZLib and comprises two Pas files along with a directory full of C source and header files, as well as some Obj files which can be linked into your Delphi application. ZLib.dcu and ZLibConst.dcu are also installed in the \Borland\Delphi5\Lib directory.

A quick look at ZLib.pas reveals two interfaces into the compression routines: An object-based interface and a single call function.

The object-based interface is shown below:

// Compression TCompressionStream = class(TCustomZlibStream) private function GetCompressionRate: Single; public constructor Create(CompressionLevel: TCompressionLevel; Dest: TStream); destructor Destroy; override; function Read(var Buffer; Count: Longint): Longint; override; function Write(const Buffer; Count: Longint): Longint; override; function Seek(Offset: Longint; Origin: Word): Longint; override; property CompressionRate: Single read GetCompressionRate; property OnProgress; end; // Decompression TDecompressionStream = class(TCustomZlibStream) public constructor Create(Source: TStream); destructor Destroy; override; function Read(var Buffer; Count: Longint): Longint; override; function Write(const Buffer; Count: Longint): Longint; override; function Seek(Offset: Longint; Origin: Word): Longint; override; property OnProgress; end;

The procedural interface is shown next:

procedure CompressBuf( const InBuf: Pointer; InBytes: Integer; out OutBuf: Pointer; out OutBytes: Integer); procedure DecompressBuf( const InBuf: Pointer; InBytes: Integer; OutEstimate: Integer; out OutBuf: Pointer; out OutBytes: Integer);

We decided that the procedural interface would be easier to implement for our purposes, we just had to create a wrapper that would give us the option of choosing between buffer, stream, string and file-based compression and decompression.

An interface along the lines of the one shown below and was designed to give us maximum flexibility.

TtiCompressAbs = class( TObject )

protected

// Stream compression and decompression

function CompressStream( pFrom : TStream ;

pTo : TStream ) : real ; virtual ; abstract ;

procedure DecompressStream( pFrom : TStream ;

pTo : TStream ) ; virtual ; abstract ;

// Buffer compression and decompression

function CompressBuffer( const pFrom: Pointer ;

const piFromSize : Integer;

out pTo: Pointer ;

out piToSize : Integer) : real ; virtual ; abstract ;

procedure DecompressBuffer( const pFrom: Pointer ;

const piFromSize : Integer;

out pTo: Pointer ;

out piToSize : Integer) ; virtual ; abstract ;

// String compression and decompression

function CompressString( const pFrom : string ;

var pTo : string ) : real ;

virtual ; abstract ;

procedure DecompressString( const From : string ;

var pTo : string ) ; virtual ; abstract ;

// File compression and decompression

function CompressFile( const pFrom : string ;

const pTo : string ) : real ; virtual ; abstract ;

procedure DecompressFile( const pFrom : string ;

const pTo : string ) ; virtual ; abstract ;

end ;

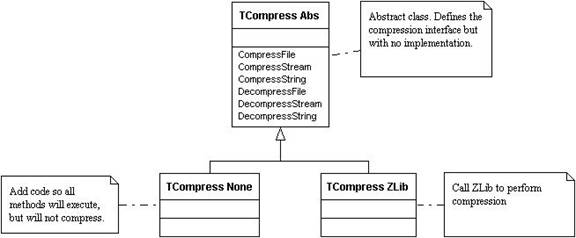

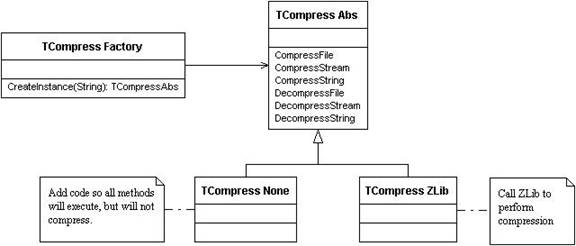

Two concrete classes where coded:

- TtiCompressZLib which implements the ZLib functionality; and

- TtiCompressNone which gives no compression.

The idea of having a compression class, which does not actually compress anything, came from studying the Null Object Pattern at a Melbourne Pattern Group meeting in August 2000. The intent of The Null Object Patter is ‘Provide a surrogate for another object that shares the same interface but does nothing. The Null Object encapsulates the implementation decisions of how to “do nothing” and hides those details from its collaborators.' The text of the (I think brilliant) Null Object Pattern can be found at http://citeseer.nj.nec.com/woolf96null.html

The full source code of each of these classes can be found on the TechInsite web site.

The class hierarchy that has been implemented in the demo application is shown in below and can be found in the units tiCompressAbs.pas, tiCompressNone.pas and tiCompressZLib.pas on the companion disk.

Creating a Concrete Instance of the Adaptor

Now that we have coded our class hierarchy, we want to create an instance of the concrete class for use. The first method we can use is to specify the appropriate concrete class directly in code. This will lock us into using this class from design time, through compile to run-time. We may do something like:

Var lCompress : TtiCompressAbs ; Begin lCompress := TtiCompressZLib.Create ; lCompress.CompressString( pStringIn, pStringOut ) ;

Creating From a Class Reference

If we want to make it easier to vary the way our application behaves, we would be better off using a class reference to create our concrete instances. If you have not used a class reference before, you can learn more about the in the Delphi Help under ‘Class Reference'.

Taking our abstract compression class, a class reference declaration would look like this:

Type TtiCompressAbs = Class( TObject ) // more... TtiCompressClass = Class of TtiCompress ;

(This line of code can be found in tiCompress.pas on the companion disk)

Using a class reference lets us write code like this:

Var lCompresClass : TtiCompressClass ; lCompress : TtiCompressAbs ; Begin // Notice this is a reference to a class type, // not an instance of the class. lCompressClass := TtiCompressZLib ; try lCompress := lCompressClass.Create ; // Use the instance...;

This code is not very useful, but it does illustrate the concept. If we have our three classes declared in their own units like this:

TtiCompressAbs - in tiCompressAbs.pas; TtiCompressZLib - in tiCompressZLib.pas; and TtiCompressNone - in tiCompressNone.pas

then we start to see some useful functionality.

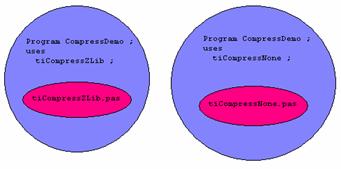

If tiCompressAbs.pas has a globally visible variable of type TtiCompressClass, then we can set this variable in the initialization section of both tiCompressZLib.pas and tiCompressNone.pas. If we always create the concrete instances of the compression object through the class reference, we can control the behaviour of our application by linking in either tiCompressZLib.pas or tiCompressNone.pas.

TiCompressAbs.pas will contain the following in its interface section:

// A globally visable variable to hold an instance of the // compression class we will be using in the application. var gTiCompressClass : TtiCompressClass ; function CreateDefaultCompress : TtiCompressAbs ; implementation // A helper function to create a compression object, with some // checking before they are created function CreateDefaultCompress : TtiCompressAbs ; begin Assert( gTICompressClass <> nil, 'gTICompressClass not assigned' ) ; Result := gTICompressClass.Create ; End ;

In tiCompressZLib.pas and tiCompressNone.pas, we will have the following lines of code in the initialization sections:

// tiCompressZLib.pas initialization gtiCompressClass := TtiCompressZLib ; // tiCompressNone.pas initialization gtiCompressClass := TtiCompressNone ;The behaviour of the application can be changed by changing a single line of code in the project's DPR file like this.

Program CompressDemo ; Uses TiCompressZLib, // This will give the application ZLib behaviour // TiCompressNone // This will give the application no compression behaviour ;

This is illustrated in below:

In summary, this technique is useful for easily changing the behaviour of an application at compile time.

Creating from a Factory

An article on The Factory Pattern was published in September 1999 in edition 49 of The Delphi Magazine. To recap, the Factory can be implemented in Delphi as a TList of objects that map a string that identifies a class to a class reference that can be used to create an instance of the class.

To allow the behaviour of the application to be changed at runtime, we must create a class that maps a string identifier to a class reference. We then build a list of these mappings when the application initialises. To create a concrete instance of a class, we search the list for the appropriate mapping, and then use its class reference to return an instance.

We shall look at the two classes we use to achieve this: the class mapping, and the Factory. The interface and implementation of the class mapping (TtiCompressClassMapping) is shown below:

Interface

// A class to hold the TtiCompress class mappings. The Factory maintains

// a list of these and uses the CompressClass property to create the objects.

// ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TtiCompressClassMapping = class( TObject )

private

FsMappingName : string;

FCompressClass : TtiCompressClass;

public

Constructor Create( const pMappingName : string ;

pCompressClass : TtiCompressClass ) ;

property MappingName : string read FsMappingName ;

property CompressClass : TtiCompressClass read FCompressClass ;

end ;

implementation

// Overloaded constructor - used to create an instance

// of TtiCompressClassMapping and to preset it's properties.

constructor TtiCompressClassMapping.Create(const pMappingName: string;

pCompressClass: TtiCompressClass);

begin

inherited Create ;

FsMappingName := pMappingName ;

FCompressClass := pCompressClass ;

end;

TtiCompressClassMapping comprises two properties, MappingName of type string and CompressClass of type TtiCompressClass. There is an overloaded constructor that lest us create an instance of TtiCompressClassMapping and preset its properties in a single call.

The second class we shall use is called TtiCompressFactory and is basically just a wrapper around a TObjectList with a method to register a class mapping. There is also a function that we can call to create a concrete instance of a TtiCompressAbs. This code is shown below:

Interface

// Factory Pattern - Create a descendant of the TtiCompress at runtime.

TtiCompressFactory = class( TObject )

private

FList : TObjectList ;

public

constructor Create ;

destructor Destroy ; override ;

procedure RegisterClass( const pCompressionType : string ;

pCompressClass : TtiCompressClass ) ;

function CreateInstance( const pCompressionType : string )

: TtiCompressAbs ; overload ;

end ;

implementation

constructor TtiCompressFactory.Create;

begin

inherited ;

FList := TObjectList.Create ;

end;

destructor TtiCompressFactory.Destroy;

begin

FList.Free ;

inherited;

end;

// Register a TtiCompress class for creation by the Factory

procedure TtiCompressFactory.RegisterClass(

const pCompressionType: string; pCompressClass: TtiCompressClass);

var

i : integer ;

begin

for i := 0 to FList.Count - 1 do

// SameText is an undocumented function in SysUtils.pas. There is a note

// accompaning the source code which says:

// SameText compares S1 to S2, without case-sensitivity. Returns true if

// S1 and S2 are the equal, that is, if CompareText would return 0. SameText

// has the same 8-bit limitations as CompareText }

if SameText( TtiCompressClassMapping( FList.Items[i] ).MappingName,

pCompressionType ) then

raise exception.CreateFmt( 'Compression class <%s> already registered.',

[pCompressionType] ) ;

FList.Add( TtiCompressClassMapping.Create(

pCompressionType, pCompressClass )) ;

end;

// Call the Factory to create an instance of TtiCompress

function TtiCompressFactory.CreateInstance( const pCompressionType: string) : TtiCompressAbs;

var

i : integer ;

begin

result := nil ;

for i := 0 to FList.Count - 1 do

if SameText( TtiCompressClassMapping( FList.Items[i] ).MappingName, pCompressionType ) then

begin

result := TtiCompressClassMapping( FList.Items[i] ).CompressClass.Create ;

Break ; //==>

end ;

raise exception.CreateFmt( '<%s> does not identify a registered compression class.',

[pCompressionType] )) ;

end;

The key methods are RegisterClass and CreateInstance. Register Class takes two parameters: a string to identify the compression type, and a class reference that can be used to create the compression object. RegisterClass is called in the initialisation section of both tiCompressZLib.pas and tiCompressNone.Pas and typically look like this:

// In tiCompressZLib.pas initialization // Register the TtiCompressZLib class with the Factory gCompressFactory.RegisterClass( 'Zlib Compression', TtiCompressZLib ) ; // In tiCompressZLib.pas initialization // Register the TtiCompressNone with the CompressFactory gCompressFactory.RegisterClass( 'No Compression', TtiCompressNone ) ;

The code inside RegisterClass first scans the list of TtiCompressClassMapping(s) looking for an already created instance, then raises an exception if one was found (this means a programmer was trying to register a mapping under the same name more than once.) Next, an instance of TtiCompressClassMapping is created with its pre-assigned properties and is added to the list.

The code inside CreateInstance performs the same search for a registered class, then when found, calls Create against the mapped class reference and returns a concrete instance of the appropriate compression class.

We only want one instance of the compression to exist in memory at any time, so we implement it as the Singleton Pattern. I do this using a variable with unit wide visibility, which is hidden behind a globally visible function. This is not a true singleton as it is possible to create more than one instance of TtiCompressFactory, and it is also possible to free the Factory before the application terminates. (Some more ‘pure' implementations of the Singleton Pattern are discussed in issues 41 and 44 of The Delphi Magazine). My implementation of the compression Factory as a singleton is shown below:

Interface

// The CompressFactory is a singleton which is implemented as a variable with

// unit wide visibility hidden behind a globally visible function.

function gCompressFactory : TtiCompressFactory ;

implementation

var

// A var to hold our single instance of the TtiCompressFactory

uCompressFactory : TtiCompressFactory ;

function gCompressFactory : TtiCompressFactory ;

begin

if uCompressFactory = nil then

uCompressFactory := TtiCompressFactory.Create ;

result := uCompressFactory ;

end ;

initialization

// Do not bother creating an instance of TtiCompressFactory here, it will

// be created on demand when it is first used.

finalization

// Free the TtiCompressFactory in the finalization section

uCompressFactory.Free ;

When we want to create and use a compression object, we call the Factory like this:

Var

lCompress : TtiCompressAbs ;

begin

// We can dynamically change the type of compression

// by passing a different string here

lCompress := gCompressFactory.CreateInstance( 'ZLib Compression ) ;

try

// use the encryption object

finally

lCompress.Free ;

end ;

end ;

In summary, we have extended our compression class hierarchy with a Factory as shown in the UML below:

To recap, we have build:

- An abstract compression class that defines the interface, but has no implementation. This is contained in the unit tiCompress.pas.

- A ZLib compression class, which is contained in the unit tiCompressZLib.

- A No compression class, which is an implementation of the Null Object Pattern which has the same interface as ZLib compression but performs no compression. This is contained in the unit tiCompressNone.pas.

- A Factory to control which concrete compression class to create at runtime. This is contained in listing tiCompress.pas.

- We also create a demonstration application with a main form that will let us test the various methods on the different compression classes.

Adapting Data Access Components

Adapting a compression or encryption class is useful, but these algorithms are seldom core to the functionality of an application. Data access components are core to most business applications, but their interfaces are usually complex and have many dependencies. Most data access components are descendants of TDataSet and can be interacted with in code, or wired up to data aware controls.

If you're not bothered about loosing the ability to connect to a data aware control via a TDataSource, there are some benefits in adapting the interface of Delphi's data access components. My class hierarchy of data access components is shown in the UML below:

This shows the adaptors used in the TechInsite persistence framework. The starting point is the virtual abstract class TtiQuery which implements navigation and field access methods, much the same as the TDataSet does. The TtiQueryBDE implements BDE style connectivity via a TQuery and has been tailored for both Interbase and Paradox connectivity in the TtiQueryBDEInterbase and TtiQueryBDEParadox. TtiQueryDOA gives Oracle access via the DOA (‘Direct Oracle Access') components, while the TtiQueryIB gives Interbase connectivity via IBObjects.

By now, you are probably thinking that this is all a waste of effort as this functionality is all wrapped up in the TDataSet ancestor. Well, a TDataSet brings along considerable fat and for optimised Oracle access, it's best to use a component that is not a TDataSet descendent.

The TtiQueryRemoteHTTP and TtiQueryRemoteDCOM give similar functionality to using the TClientDataSet with MIDAS without the need to deploy MIDAS and pay MIDAS licences. This architecture has been use to build an application that can connect directly to Oracle from behind the companies firewall. With the flick of a command line switch, the same application can communicate with the database via a web server over port 80 using HTTP.

This framework makes it possible to write code like:

Var lQueryIB : TtiQueryIB ; lQueryXML : TtiQueryLocalXML ; lCustomer : TCustomer ; begin lCustomer := TCustomer.Create ; lCustomer.OID := 100 ; lQueryIB := TtiQueryIB.Create ; lQueryIB.Read( lCustomer ) ; lQueryXML := TtiQueryLocalXML.Create ; lQueryXML.Save( lCustomer ) ;

This means the persistence layer can be swapped at run-time that is very difficult to do with the component on form style of developing. The full source of the TechInsite persistence framework, along with a demonstration of this technique is available for free from http://www.tiopf.com/

Summary

In this chapter we have studied the Adaptor Pattern in some detail, and have also revisited the Factory Pattern and glimpsed at the Null Object Pattern. We have seen how the Adaptor, Factory and Null Object Patterns can be used to together to delay the implementation of a complex algorithm, or to allow one algorithm to be replaced with another at compile time or run time.

We have seen how to wrapper the ZLib compression routines to give a more convenient interface, and explored the idea of wrappering data access components to reduce our dependency on a specific vendor's data access API.

Good luck implementing the Adaptor Pattern and please let me know of your experiences on the EMail address below.